A gigantic observatory buried in the Antarctic ice has helped scientists trace elusive particles called neutrinos back to their origins at the heart of a nearby galaxy—offering a new way to study a supermassive black hole shrouded from view.

For the first time, an international team of scientists have found evidence of high-energy neutrino emission from NGC 1068, also known as Messier 77, an active galaxy in the constellation Cetus and one of the most familiar and well-studied galaxies to date. First spotted in 1780, this galaxy, located 47 million light-years away from us, can be observed with large binoculars. The results, also published (Nov. 4, 2022) in Science, were shared today in an online scientific webinar that gathered experts, journalists, and scientists from around the globe

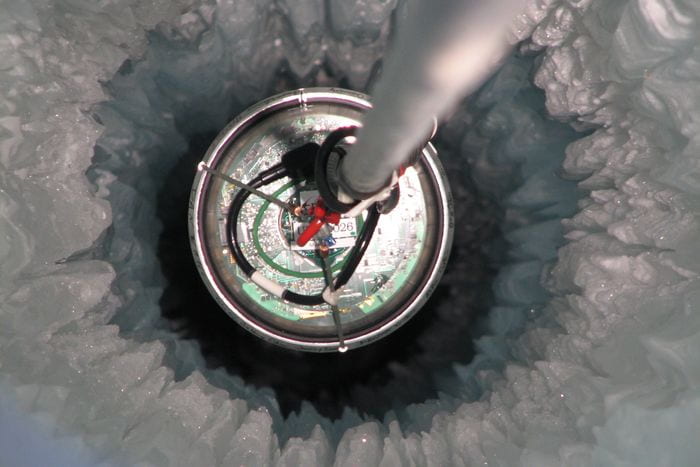

The detection was made at the National Science Foundation-supported IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a massive neutrino telescope encompassing 1 billion tons of instrumented ice at depths of 1.5 to 2.5 kilometers below Antarctica’s surface near the South Pole. This unique telescope, which explores the farthest reaches of our universe using neutrinos, reported the first observation of a high-energy astrophysical neutrino source in 2018. The source, TXS 0506+056, is a known blazar located off the left shoulder of the Orion constellation and 4 billion light-years away.

“One neutrino can single out a source. But only an observation with multiple neutrinos will reveal the obscured core of the most energetic cosmic objects,” says Francis Halzen, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and principal investigator of IceCube. He adds, “IceCube has accumulated some 80 neutrinos of teraelectronvolt energy from NGC 1068, which are not yet enough to answer all our questions, but they definitely are the next big step towards the realization of neutrino astronomy.”

Unlike light, neutrinos can escape in large numbers from extremely dense environments in the universe and reach Earth largely undisturbed by matter and the electromagnetic fields that permeate extragalactic space. Although scientists envisioned neutrino astronomy more than 60 years ago, the weak interaction of neutrinos with matter and radiation makes their detection extremely difficult. Neutrinos could be key to our queries about the workings of the most extreme objects in the cosmos.

“Answering these far-reaching questions about the universe that we live in is a primary focus of the U.S. National Science Foundation,” says Denise Caldwell, director of NSF’s Physics Division.

As is the case with our home galaxy, the Milky Way, NGC 1068 is a barred spiral galaxy, with loosely wound arms and a relatively small central bulge. However, unlike the Milky Way, NGC 1068 is an active galaxy where most radiation is not produced by stars but due to material falling into a black hole millions of times more massive than our Sun and even more massive than the inactive black hole in the center of our galaxy.

NGC 1068 is an active galaxy—a Seyfert II type in particular—seen from Earth at an angle that obscures its central region where the black hole is located. In a Seyfert II galaxy, a torus of nuclear dust obscures most of the high-energy radiation produced by the dense mass of gas and particles that slowly spiral inward toward the center of the galaxy.

“Recent models of the black hole environments in these objects suggest that gas, dust, and radiation should block the gamma rays that would otherwise accompany the neutrinos,” says Hans Niederhausen, a postdoctoral associate at Michigan State University and one of the main analyzers of the paper. “This neutrino detection from the core of NGC 1068 will improve our understanding of the environments around supermassive black holes.”

NGC 1068 could become a standard candle for future neutrino telescopes, according to Theo Glauch, a postdoctoral associate at the Technical University of Munich (TUM), in Germany, and another main analyzer.

“It is already a very well-studied object for astronomers, and neutrinos will allow us to see this galaxy in a totally different way. A new view will certainly bring new insights,” says Glauch.

These findings represent a significant improvement on a prior study on NGC 1068 published in 2020, according to Ignacio Taboada, a physics professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the spokesperson of the IceCube Collaboration.

“Part of this improvement came from enhanced techniques and part from a careful update of the detector calibration,” says Taboada. “Work by the detector operations and calibrations teams enabled better neutrino directional reconstructions to precisely pinpoint NGC 1068 and enable this observation. Resolving this source was made possible through enhanced techniques and refined calibrations, an outcome of the IceCube Collaboration’s hard work.”

The improved analysis points the way toward superior neutrino observatories that are already in the works.

“It is great news for the future of our field,” says Marek Kowalski, an IceCube collaborator and senior scientist at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, in Germany. “It means that with a new generation of more sensitive detectors there will be much to discover. The future IceCube-Gen2 observatory could not only detect many more of these extreme particle accelerators but would also allow their study at even higher energies. It’s as if IceCube handed us a map to a treasure trove.”