That’s No Exomoon: Astrophysicists Reveal Method For Finding Exoplanets’ Satellite Neighbors

It’s a famous “Star Wars: Episode IV” scene, so famous it has its own internet meme: Luke Skywalker mistakes the Death Star for a moon, but Obi-Wan Kenobi corrects him, accompanied by an ominous stab of John Williams’ music: “That’s no moon.”

Billy Quarles, research scientist in the School of Physics and member of Georgia Tech’s Center for Relativistic Astrophysics (CRA), couldn’t resist the comparison when preparing a summary of new research on exomoons he conducted with fellow School of Physics colleague, assistant professor Gongjie Li, also a member of the CRA.

“Decades later, life imitates art where one frontier in astronomy is to detect a moon orbiting an exoplanet, or exomoon,” Quarles says in his summary of their work, to be published this month in Astrophysical Journal Letters and co-authored with Marialis Rosario-Franco, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Their letter establishes a framework for finding out whether exoplanets might have moons, and they had a chance to test that on the work of two Canadian astronomers who say there may be moons orbiting six exoplanets discovered with the Kepler Space Telescope.

Quarles’ and Li’s results? To paraphrase Obi-Wan, when it comes to four of the six exoplanets, those aren’t exomoons.

Exomoons Rising

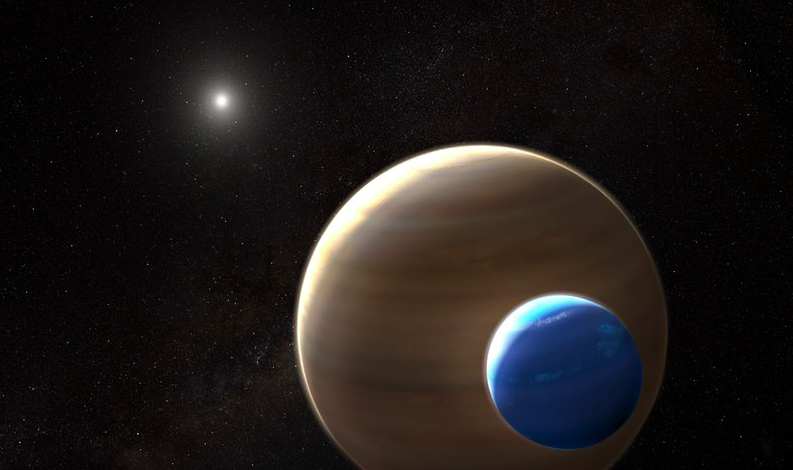

Exoplanets are planets found outside our solar system. Telescopes couldn’t capture their image, so science had to wait for 1990s-era technology before confirming their existence. If moons of these planets do exist, they’re the ones now waiting for their moment in the scientific spotlight.

Exoplanets were first confirmed with improvements to measurements of radial velocity, which is the gravitational relationship between star and planet. “It seems that the detection of exomoons are waiting for a similar technological advance,” Quarles says.

The Kepler Space Telescope was launched in 2009 with the mission of finding exoplanets. Any stars found by it that may be harboring exoplanet candidates are first called Kepler Objects of Interest (KOI).

Earlier this year, University of Western Ontario astronomers Chris Fox and Paul Wiegert theorized that six exoplanets found via Kepler could be hosting exomoons.

“They deduced the possible existence of exomoons by carefully measuring the difference in transit times for these exoplanets, where variations can indicate the presence of unseen bodies,” Quarles says. Transits are when a planetary body crosses in between a larger body and whomever is doing the observing.

“They found variations and alerted the astronomical community. Since they could not confirm the exomoons directly, Fox and Wiegert admit that nearby planets could also be responsible for those variations, where the planet is tilted just enough relative to us so that it does not transit its host star,” he says.

All this is why exomoons “are on the frontier of detectability using current technologies, and theoretical constraints should be considered in their search,” Quarles says.